Part II – Bali 1928: Research, Restoration, Repatriation, and the Future

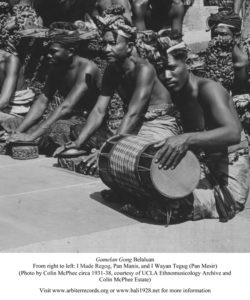

In 2000, not long after Edward Herbst first acquired access to some of the 1928 Odeon-Beka recordings, he visited composer Wayan Beratha, son of the late Madé Regog, one of the major Balinese composers of that time. Together, they listened to the many tracks recorded in his village, Belaluan. When he heard one, Curik Ngaras (Starlings Kissing), Beratha laughed and said, “I haven’t heard this since I was a kid.” Herbst gave him a cassette and within a week he learned that Beratha had already taught the composition to a children’s gamelan in his village.

This kind of immediate and deep personal response from musicians and singers, old and young, led to our commitment to create a repatriation project of all the extant recordings from 1928. In 1980 Andrew Toth wrote a discography listing ninety-eight of the matrices (sides of the 78 rpm discs). During the 1980s and 1990s Philip Yampolsky was able to locate 101 matrices at various archives in Indonesia, the U.S. and the Netherlands. Yampolsky shared this information with Arbiter’s director Allan Evans and Herbst, facilitating a worldwide effort to access and reissue each and every 78 disc.

Fifty-six 78-rpm discs (111 sides, each three minutes) are currently known to exist. Up until the publications and dissemination resulting from this project, the only recordings generally available to Balinese artists, performers, scholars and the public have been of music released by the indigenous cassette industry beginning in the 1970s.

Significant collections exist in Indonesian museums but remain ignored. Sana Budaya, the national museum in Yogyakarta, has numerous 78s but has not had a turntable for 60 years. Similarly, the Museum Nasional in Jakarta still does not have the technology to make copies from the old records. Herbst and his Indonesian colleagues eventually gained access to both collections using a turntable he brought from New York. His U.S. publishing partner, Arbiter of Cultural Traditions, led by Allan Evans, has been uniquely suited to the task of audio restoration with its Sonic Depth Technology that combines unparalleled expertise in unearthing the sounds buried in old 78 rpm shellac discs as well as the most up-to-date software technologies.

Adding 1930s photographs and films to the trove of recordings has allowed Herbst and his Balinese research team to make remarkable discoveries using these previously unavailable resources. A Balinese friend saw a 1930 photo from the Claire Holt Collection at the New York Public Library, and told Herbst one of the dancers was a “hundred-year old” who still lived up the road. The next day they visited the elderly performer, Mémen Redia (a.k.a. Ni Wayan Pempen), and when she saw the photo she said, ‘Sing tiang’ (‘That’s not me.’) But Herbst knew she had been part of this same group, Jangér Kedaton, and asked if she would like to hear some old recordings and when she heard the CD on his boom-box, she exclaimed, ‘Niki tiang’ (‘That’s me.’)

Adding 1930s photographs and films to the trove of recordings has allowed Herbst and his Balinese research team to make remarkable discoveries using these previously unavailable resources. A Balinese friend saw a 1930 photo from the Claire Holt Collection at the New York Public Library, and told Herbst one of the dancers was a “hundred-year old” who still lived up the road. The next day they visited the elderly performer, Mémen Redia (a.k.a. Ni Wayan Pempen), and when she saw the photo she said, ‘Sing tiang’ (‘That’s not me.’) But Herbst knew she had been part of this same group, Jangér Kedaton, and asked if she would like to hear some old recordings and when she heard the CD on his boom-box, she exclaimed, ‘Niki tiang’ (‘That’s me.’)

It quickly became clear that she was the 10-year-old solo singer for six of the tracks from 1928. She then identified herself on Herbst’s laptop in 1931 film footage shot by Miguel Covarrubias. Most importantly, she also remembered the lyrics to all the songs, correcting earlier transcriptions, and explained that each song was allowed just one take, due to the cost of the recording equipment.

Herbst’s research team of Balinese performer-scholars includes faculty members of the Indonesian Institute of Arts (ISI-Bali) and Udayana University. They have travelled throughout Bali, visiting and getting to know singers, musicians, dancers, rice farmers, Brahmana priests and “commoner” temple priests, many of them well into their 90s. Aided by these previously inaccessible audio-visual treasures, the researchers have been able to rekindle memories. The recollections of these old performers and their descendants are now offering keys that younger Balinese artists are using to revive lost traditions and create new work inspired by these recordings, photographs and films.

Herbst and his Indonesian colleagues determined that merely establishing archives online or in an Indonesian university or library would not allow for access by a broad public. Balinese arts, especially music and dance with continuing ties to local religious rituals, are still deeply decentralized into village culture. Few artists from these environments are comfortable in institutional settings and almost all lack online access beyond their smart phones.

So the repatriation team chose instead to publish the materials and arrange for them to be sold at extremely affordable prices and also to provide them free to village performance clubs, libraries, universities, conservatories, regional arts centers, independent teachers as well as genealogical and artistic descendants of the 1928 artists. This kind of broad and readily accessible dissemination allows the audio-visual resources to pollinate in diverse communities, an approach that is proving essential for meaningful repatriation of this work in Bali.

Herbst and his research team continue to explore a variety of timely topics on Bali more deeply. They have started a project to bring together the most current discoveries in archaeology of Bronze-Age Bali with the aesthetic evolution and technology of Balinese musical instruments and acoustics. They also have been exploring the ancient interpenetration of Balinese music and dance with the natural environment, through both everyday wet-rice agriculture and ritual activities.

An additional compelling interest is the fast-disappearing tradition of Sasak Muslim singing in Lombok and East Bali and its profound influence on early 20th-century Balinese performance, which has always been principally associated with Hindu, Buddhist and animist practices.

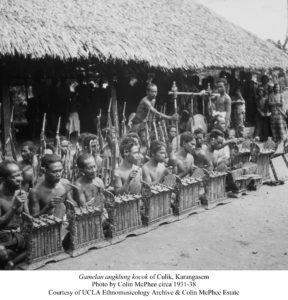

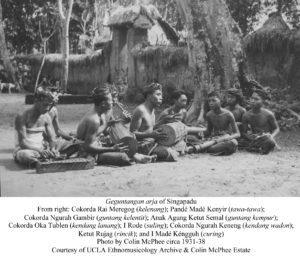

One essential challenge they continue to tackle is the anonymity and exoticism arising from photographs and films of the pre-World-War-II era. Most of the Balinese musicians and dancers would have remained nameless without penetrating research that has endowed the artists of the past with identity and personal histories, indeed the very personhood that empowers and animates their genealogical and artistic descendants to learn from and enjoy the resources to their fullest potential.

This is not just a problem of the past. The Internet is full of videos and photographs with either erroneous, misleading – or no information at all – about the material being presented. Through necessity, Herbst and team have developed an alternative style of presenting archival materials in a contextual, respectful, and technically up-to-date way. To accomplish this, they developed a style of embedding meta-data into the JPEG, PDF or video file so that the names of individuals represented, as well as the photographer-filmmaker, and the archive giving permission, are inseparable from the visual content.

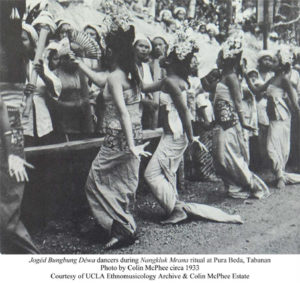

Herbst is especially intrigued by the potential for further research into the deep relationship between Balinese culture and agriculture and ecology. A film sequence shot by Colin McPhee had been confusing and unrecognizable to all Balinese viewers but ultimately proved to be evidence of an earlier synergy between music and dance with wet-rice agriculture and religious practice. These relationships, which coalesce to promote balance between humans, spirit, and nature (Tri Hita Karana), are still present in Bali, but rapidly disappearing. Some of the team’s most surprising research findings are in the region that includes Jatiluwih, a UNESCO Heritage Site for its “Cultural Landscape” preservation and sustainable management of rice cultivation.

After extensive fieldwork, Herbst, says, “We located the agricultural temple where the ceremony was held in 1933, and upon viewing our films and photographs together, learned from its priest that it was in fact a long-forgotten ritual dance performed within a ceremony for the purpose of reviving health and harmony in the rice fields by dissolving visible and invisible destructive entities and returning them to the earth to be revivified as forces of growth and abundance.” Inspired by the archival films, artists and religious leaders of the temple, Pura Beda (Bedha), built around the fifth century A.D. are proposing a revival of the ritual dance.

One composition recorded in 1928 was a contemporary re-imagining and re-contextualizing of an ancient, beautiful, and complex genre evoking the sounds of a variety of frogs and toads. Working with biologists, Herbst and his team analyzed sound recordings and identified different species associated with this music. At present this musical tradition of génggong ‘jew’s harp ensemble’ is more threatened than the enggung amphibia of the rice fields that inspire it, but the attention this research is bringing to this music is helping to stimulate a revival, generating invitations for these musicians to perform at festivals in Bali. This awareness of Bali’s artistic history as a key tool for preserving the island’s spiritual and physical ecosystem is one of the results of this research that can only take place through lengthy conversation and dialog with practitioners. It will receive closer examination and be a principal focus of the forthcoming book.

As people increasingly observe and discuss how despoiled the island has become with rampant development, severe depletion of the water table, species reduction resulting from the use of pesticides, and the loss of rice fields, the films are stimulating awareness of how agrarian society and a thriving environment can nurture Bali’s unique artistic and cultural life – and how a thriving cultural life helps to preserve ecological integrity.