Bali 1928 – Repatriating Bali’s Earliest Music Recordings, 1930s Films and Photographs

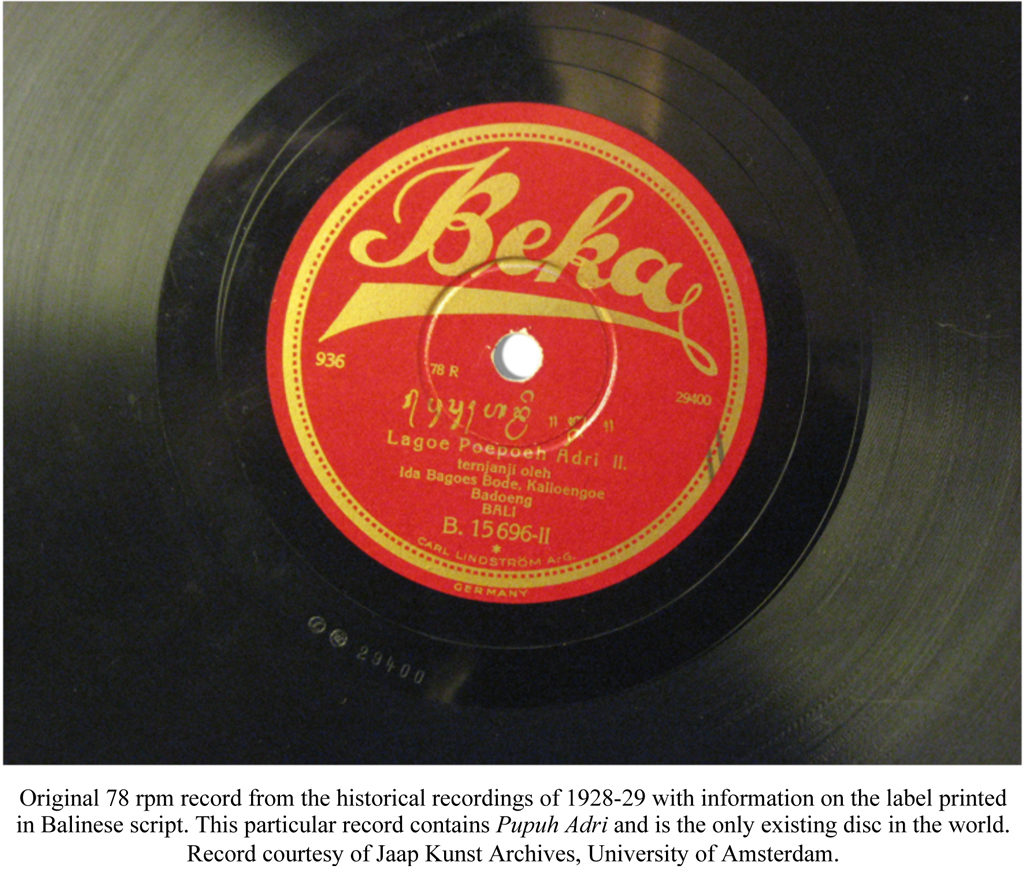

In 1928 Odeon and Beka produced the only recordings of Balinese music made in Bali and released prior to World War II. Fifty-six of the original 78-rpm records (111 sides) are known to have survived. Recovering them all required research in archives, libraries, universities and personal collections in Asia, Europe, and North America.

Canadian composer Colin McPhee first heard these recordings in New York in the winter of 1930-31, and they inspired his research in Bali over the course of the next eight years. McPhee, in his memoir, A House in Bali, recalled how in 1931 one frustrated European shopkeeper entrusted to sell the records in Bali smashed his entire inventory.

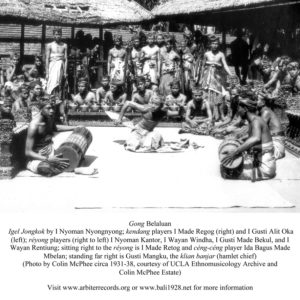

Beginning in 2000, American ethnomusicologist Edward Herbst and New York’s Arbiter of Cultural Traditions began a multi-year research project to find, document, understand, explain, restore, re-release, and repatriate all of this music. Once that work was underway, he found it was possible as well to relate much of the music of 1928 to silent films of the same musicians and their ensembles’ dancers shot in the 1930s by McPhee, Mexican artist and writer Miguel Covarrubias, and Swedish dance pioneer Rolf de Maré with anthropologist/dance ethnographer Claire Holt.

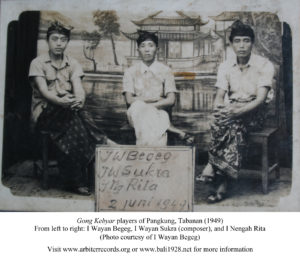

This music represents a remarkable diversity of new and ancient genres of gamelan and vocal music. Combined with more than four hours of the previously unavailable silent film from the 1930s, the recovered work offers the only documentation of seminal early 20th-century Balinese master musicians, dancers and innovators as well as styles and genres that have disappeared.

The sound and film recordings provide an unprecedented audio-visual experience of the late 1920s to the late 1930s, a decade when four factors converged to create both an efflorescence of Balinese artistic creativity and a loss of ancient traditions. The first of these historic events was the rapid decline and fall of ancient Balinese regional kingdoms. The second was the trauma of Dutch conquest in 1908 and the ensuing colonial administration of South Bali that hastened their fall and replaced their political power. As a result, much of the creation of music, dance, and arts moved from the royal courts to local villages and their clubs and associations, and emerging performance styles reflected the tastes of common Balinese audiences. And the arrival of Bali’s first wave of Western visitors gave rise to new genres, new audiences, and new influences, including emerging 20th-century media, which ensured that the world would learn of this compelling culture.

Today, Balinese scholars and artists suggest that with the empirical evidence we now have in the 1928 recordings, understanding of the social dynamics and creative impetus of 20th century Balinese aesthetics and culture is far beyond anything previously thought possible. These circumstances of loss, rediscovery, re-acquisition and revival have broad implications to inspire and inform repatriation projects elsewhere in Indonesia and worldwide.

Herbst and his Balinese and American research partners designed the project to ensure that these resources will be widely available in accessible formats, leading to further research, dissemination, and use by Indonesian and international artists, teachers, scholars, and researchers. Their restoration, dissemination and repatriation efforts have resulted in publication of five volumes in Bali including CD, DVD and cassette formats, as well as CDs in English in New York and websites in both countries. (For more information, see the Music + Films pages.)

As principal investigator, Herbst has been project director and coordinator, ethnomusicologist, researcher and writer of historical, analytical, and extensive interpretive notes included as PDF files for each volume in both English and Indonesian.

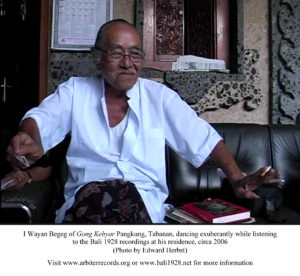

Documentation of field research based on these recordings, as well as photographs and rare films from the 1930s, constitute another dimension of repatriation by giving voice to Bali’s oldest living generation, bringing to light their disappearing traditions and newly-emerging, truly revolutionary aesthetics as well as their personal creative narratives, all in the context of competition and cooperation in colonial and post-colonial Bali. The research team’s ability to capture the memories of many of these near-centenarians has underscored the urgency of adding their knowledge to these newly accessible audio-visual resources.

The next phase of the project will see completion of a book that includes edited and updated versions of all five essays, previously formatted as PDFs. The book will also focus on the dialogic research and repatriation strategies used in this project, and the broader imperatives of a repatriation process facilitated by collaboration among foreign and indigenous artists and scholars.

Ongoing Outreach and Research

Herbst and Balinese colleagues are engaged in dissemination and public outreach activities in Indonesia to increase awareness of cultural memory, personal narratives and the importance of empirical historical resources available through repatriation of arts-related archives. Additionally, international gatherings and presentations in other countries are being scheduled.

A new Bali 1928 and Library of Congress-to-Bali Repatriation Project initiative continuing into 2023-2024 includes Gregory Bateson’s (1936-39) and Jane Belo’s (1931-39) film footage and photographs from Bali, complemented by field notes by Margaret Mead, Bateson and Belo. This project involves further research amongst centenarians and will result in publication, public presentations, and dissemination of the films, edited and restored, in Bali and internationally.

For more on these activities, see the Events + News pages.